The fast-paced techno-thriller, ‘2034: A Novel of the Next World War,’ offers an all too believable scenario for a US-China clash, but misses the mark on Beijing

By Matt Brazil, from www.spytalk.co

The possibility of a future clash between American and Chinese forces, and how to avoid another disastrous world war, are among the most debated issues in Washington.

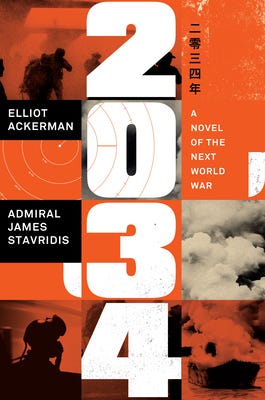

Now comes 2034: A Novel of the Next World War. The story tackles the prospect of a future war head-on in a rapid-fire narrative that, in the mold of Tom Clancy’s best military techno-thrillers, features present and soon-to-come cyber combat as a key weapon in a military showdown between the U.S. and China. Penned by retired four-star admiral James Stavridis, a former supreme commander of NATO, among many other high callings, and Elliot Ackerman, a much lauded author and Marine combat veteran of Afghanistan, 2034 arrives as Washington policymakers, awakened by an emboldened China, hold hearings to seriously consider potential scenarios for a Beijing grab of Taiwan: an across-the-beach invasion that makes the island’s cities unlivable, and an “all means short of war” intimidation campaign that forces Taiwan into voluntary surrender, suborned like Hong Kong under the “one country, two systems” model, thereby sparing its population and economy mass casualties.

The persuasive realism of 2034’s well informed narrative has brought it wide, well deserved acclaim. From its foreboding opening pages to its shuddering, frightening, and all-too-believable finish, it’s a heart stopping rush. The authors show many strengths in relating how devastating a Sino-American war would be to both nations. But the novel contains an important blind spot in its uninformed depiction of how the Chinese side actually works.

It is a concern underlined by recent war games, where one team playing the U.S. side couldn’t prevent a “red team” of Chinese forces from invading Taiwan. In those exercises, sponsored by the Pentagon-connected RAND Corporation, the U.S. suffered heavy losses of Navy warships and bases in Guam and Okinawa.

It’s been just over 70 years since Chinese and U.S. forces clashed, in Korea. Back then the People’s Liberation Army was a primitive force that was willing to suffer enormous casualties to push U.S. troops back from its border. Now, in 2021, the technology gap between Chinese and American forces has dramatically shrunk. Rapid Chinese advances in artificial intelligence, computing, aerospace, precision machining, missiles, and telecommunications technology, to name a few, make American planners wonder how long they can maintain a lead on the battlefield.

The East is Red

In the world of 2034, Chinese forces seem almost invincible, and the Americans appear not to have made a single solid technological and military advance since 2021. Oddly, despite the prominent role of Chinese cyber attacks in the novel, the National Security Agency, a crucial player in U.S. cyber operations, goes almost unmentioned, as if it doesn’t even exist. More importantly, the authors also do not mention how China would have overcome its own internal political and economic problems and mediocrity in joint force operations. Nor do they describe how Chinese forces defeat Taiwan’s considerable, U.S.-supplied defenses. The narrative simply fast forwards to Beijing’s seemingly inevitable victory, as if narrated by a Pentagon Rip Van Winkle. Heroes and a few villains, of course, dominate the story. The human toll of this theater-wide conflict is a backdrop.

And yet 2034 succeeds on many levels. The novel’s greatest strength is its convincing depiction of how both sides slide toward mutual destruction. With a great advantage in the cyber realm, the Chinese start by paralyzing U.S. forces, exploiting America’s “worship of technology,” portrayed as a crippling addiction. American Navy communications and navigation equipment fail across the Pacific. Ships are sunk. Fighters are shot down. Thousands of sailors go down in the South China Sea. Off the coast of Iran, a U.S. Navy jet is hacked by Beijing’s ally, Tehran, and brought down onto Iranian territory in a coordinated operation.

Mutual nuclear destruction of Chinese and American cities seems inevitable. America’s first woman president, oddly unnamed throughout, seems barely effective. Meanwhile, we find that India has risen to be an equal to China and America, with a corresponding ascendant role in geopolitics.

In this sense, the book does a great service by dramatically presenting the reality of growing Chinese power, especially along its periphery, amid the chilling prospect of American decline. In a field of literature that might be characterized as speculative future-conflict fiction, the authors are excellent at depicting force structures, notional technological advances and inadvertent escalation leading toward unintended disaster.

Bù Hǎo

By contrast, the book has a set of shortcomings related to China that undercut its credibility and could’ve been avoided with the help of a graduate student in China studies. There are minor issues at first, such as the inconsistent spellings of Chinese names, annoying to those who have more than a passing familiarity with the country. (Not to be picky, but Defense Minister “Chiang” uses an old spelling style; the name of the Chinese ship Wén Rui, affixed with the only tone mark in the whole book, places it above the first word, but not the second. As it is, Wén Rui could mean several things, including a general term for gnats and mosquitos.)

Then come a few shopworn tropes. A Chinese admiral, Lin Bao, ponders that he will never be allowed to become more “than a single cog in the vast machinery of the People’s Republic.” Chiang displays “his small carnivorous teeth.” An Iranian torturer allows “the three fingers of his mangled right hand to crawl crab-like toward the base” of his American victim’s neck. An Iranian doctor attending the American has “a bony face cut at flat angles like the blades of several knives”

Inevitably, it seems, there are numerous references to Sun Tzu’s Art of War, which seems to be America’s favorite shortcut to understand Chinese thinking.

Then there are some questionable assertions that a research assistant would have flagged, like the partly true but inaccurate common wisdom that in Chinese, “the words for crisis and opportunity are the same.” There’s the bonkers revelation that the Chinese admiral at the center of the story, Lin Bao, has dual U.S. and Chinese citizenship—highly unlikely since Beijing has zero-tolerance for such among its ordinary citizens, not to mention a senior military figure and party member with top secret security clearances.

There are also a few WTF moments. In one passage, Chinese forces had “converged in a noose around Chinese Taipei, or Taiwan, as the West insisted on calling it.” This is just plain wrong. Beijing regularly uses Taiwan to refer to the island, and always has. They just don’t want anyone calling Taiwan a separate nation, or—trigger warning!—uttering the reality that dares not speak its name: that there are, in all practicality, “two Chinas.”

In another passage, orders to launch an attack on the continental U.S. are passed directly from a member of the Chinese Politburo to Admiral Lin Bao instead of being documented by a Central Committee notice and sent down through the Central Military Commission—a story-stopping passage to the authors, maybe, but still: In a book where Chinese tactical decisions are a key part of the drama, there’s no explanation of such a fundamental change in Beijing’s decision making.

Later on, there’s an assassination of one of the key Chinese officials in a hotel room by State Security agents when things go bad. Again, implausible: The Chinese communists have the blood of millions on their hands, but at the top, miscreants are purged and imprisoned and, in general, executions of smaller fry are public, cast as gruesome warnings to the masses. The official’s demise might have been believable with a line about how aspects of Chinese politics had changed, but no explanations are offered.

But 2034 has other valuable elements, including the implied observation that China knows America much better than America knows China. (We must do something about that.) But the story would have benefitted by following, not just quoting, Sun Tzu’s most important maxim: “Know the enemy and know yourself, (and you) need not fear danger in one hundred battles.” (知彼知己 百战不殆, Zhī bǐ zhījǐ, bǎizhàn bùdài)

Come to think of it, in 2034’s telling, Chinese leaders would’ve been wise to follow that maxim themselves. Talk is far better than war.

Matt Brazil is the co-author, with Peter Mattis, of Chinese Communist Espionage, An Intelligence Primer. He served at the American Embassy, Beijing in the 1990s.

2034, A Novel of the Next World War, by Elliot Ackerman and Admiral James Stavridis (New York: Penguin Press, 2021)